|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cara Maria,

Cara Maria Pontes de Azevedo,Muito obrigada pelo seu e-mail.Apesar de se achar que os homens primitivos navegavam, conforme o artigo que segue em baixo:... não existem evidências concretas da navegação do Homem primitivo até às ilhas; o que existem são achados do homem primitivo em ilhas que sempre foram ilhas, como é o caso das Filipinas (de origem tectónico-vulcânica), o que leva os investigadores a indagar o como é que eles terão chegado lá... Terão sido arrastados por um tsunami ou por um tufão? Ou terão flutuado até intencionalmente com a ajuda de troncos ou jangadas? São interrogações informais, que cada vez mais e mais vão sendo levantadas, no entanto nos artigos científicos, apenas são publicados os achados. Partilho mais abaixo toda a bibliografia que tenho sobre o Homo erectus (o hominídeo mais bem-sucedido do passado) e deixo em baixo a referência aos achados feitos nas Filipinas:

> Ingicco, T., et al. “Earliest Known Hominin Activity in the Philippines by 709 Thousand Years Ago.” Nature, vol. 557, no. 7704, 2018, pp. 233–237., doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0072-8;> Détroit, F., Mijares, A. S., Corny, J., Daver, G., Zanolli, C., Dizon, E., . . . Piper, P. J. (2019). A new species of Homo from the Late Pleistocene of the Philippines. Nature, 568(7751), 181-186. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1067-9

Referências Bibliográficas acerca do Homem primitivo (assinalado a negrito as referências que dizem diretamente respeito à sua presença nas ilhas):1 - Antón, S. C., & Kuzawa, C. W. (2017). Early Homo , plasticity and the extended evolutionary synthesis. Interface Focus, 7(5), 20170004. doi:10.1098/rsfs.2017.0004

2- Antón, S. C. (2012). Early Homo. Current Anthropology, 53(S6). doi:10.1086/667695

3 - Gabounia, L., Lumley, M. D., Vekua, A., Lordkipanidze, D., & Lumley, H. D. (2002). Découverte d’un nouvel hominidé à Dmanissi (Transcaucasie, Géorgie). Comptes Rendus Palevol, 1(4), 243-253. doi:10.1016/s1631-0683(02)00032-5 (note: there is an English translation within this paper)

4 - Lordkipanidze, D., Leon, M. S., Margvelashvili, A., Rak, Y., Rightmire, G. P., Vekua, A., & Zollikofer, C. P. (2013). A Complete Skull from Dmanisi, Georgia, and the Evolutionary Biology of Early Homo. Science, 342(6156), 326-331. doi:10.1126/science.1238484

5 - Antón, S. C., Taboada, H. G., Middleton, E. R., Rainwater, C. W., Taylor, A. B., Turner, T. R., . . . Williams, S. A. (2016). Morphological variation in Homo erectus and the origins of developmental plasticity. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 371(1698), 20150236. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0236

6 - Mastu'ura, S., Kondo, M., Danhara, T., Sakata, S., Iwano, H., Hirata, T., … Aziz, F. (2020). Age control of the first appearance datum for Javanese Homo erectus in the Sangiran area. Science, 367(6474), 210-214.

7 - Anton, S. C. (2002). Evolutionary significance of cranial variation in Asian Homo erectus. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 118, 301-323.

8 - Rightmire, G. P. (2008). Homo in the Middle Pleistocene: Hypodigms, variation, and species recognition. Evolutionary Anthropology, 17, 8-21.

9 - Schwartz, J. H. (2004). Getting to know Homo erectus. Science, 305, 53-54.

10 - Walker, A. & Leakey, R. in The Nariokotome Homo erectus Skeleton (eds Walker, A. & Leakey, R.) 95–160 (Harvard Univ. Press, 1993).

11 - Jellema, L. M., Latimer, B. & Walker, A. in The Nariokotome Homo erectus Skeleton (eds Walker, A. & Leakey, R.) 294–325 (Harvard Univ. Press, 1993).

12 - Bastir, M., García-Martínez, D., Torres-Tamayo, N., Palancar, C. A., Beyer, B., Barash, A., . . . Spoor, F. (2020). Rib cage anatomy in Homo erectus suggests a recent evolutionary origin of modern human body shape. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 4(9), 1178-1187. doi:10.1038/s41559-020-1240-4

13 - Hora, M., Pontzer, H., Wall-Scheffler, C. M., & Sládek, V. (2020). Dehydration and persistence hunting in Homo erectus. Journal of Human Evolution, 138, 1-21.

14 - Rogers, A., Iltis, D., & Wooding, S. (2004). Genetic variation at the MC1R locus and the time since loss of human body hair. Current Anthropology, 45(1), 105-108

15 - Aiello, L. C., & Wheeler, P. (1995). The Expensive-Tissue Hypothesis: The Brain and the Digestive System in Human and Primate Evolution. Current Anthropology, 36(2), 199-221. doi:10.1086/204350

16 - Goren-Inbar, N. (2004). Evidence of Hominin Control of Fire at Gesher Benot Ya`aqov, Israel. Science, 304(5671), 725-727. doi:10.1126/science.1095443

17 - Carotenuto, F., Tsikaridze, N., Rook, L., Lordkipanidze, D., Longo, L., Condemi, S., & Raia, P. (2016). Venturing out safely: The biogeography of Homo erectus dispersal out of Africa. Journal of Human Evolution, 95, 1-12. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2016.02.005

18 - Abbate, E., & Sagri, M. (2012). Early to Middle Pleistocene Homo dispersals from Africa to Eurasia: Geological, climatic and environmental constraints. Quaternary International, 267, 3-19. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2011.02.043

19 - Rizal, Y., Westaway, K. E., Zaim, Y., van den Bergh, G. D., Bettis III, E. A., Morwood, M. J. … Ciochon, R. L. (2020). Last appearance of Homo erectus at Ngandong, Java, 117,000–108,000 years ago. Nature, 577, 381–385. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1863-2

20 - Brown, P., Sutikna, T., Morwood, M. J., Soejono, R. P., Jatmiko, W., Saptomo, E. W., & Awe Due, R. (2004). A new small-bodied hominin from the Late Pleistocene of Flores, Indonesia. Nature 431, 1055–1061. (doi:10.1038/nature02999)

21 - Diniz-Filho, J. A., & Raia, P. (2017). Island Rule, quantitative genetics and brain–body size evolution in Homo floresiensis. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 284(1857), 20171065. doi:10.1098/rspb.2017.1065

22 - Argue, D., Groves, C. P., Lee, M. S., & Jungers, W. L. (2017). The affinities of Homo floresiensis based on phylogenetic analyses of cranial, dental, and postcranial characters. Journal of Human Evolution, 107, 107-133. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2017.02.006

23 - Détroit, F., Mijares, A. S., Corny, J., Daver, G., Zanolli, C., Dizon, E., . . . Piper, P. J. (2019). A new species of Homo from the Late Pleistocene of the Philippines. Nature, 568(7751), 181-186. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1067-9

24 - Berger, L. R., Hawks, J., Ruiter, D. J., Churchill, S. E., Schmid, P., Delezene, L. K., . . . Zipfel, B. (2015). Homo naledi, a new species of the genus Homo from the Dinaledi Chamber, South Africa. ELife, 4. doi:10.7554/elife.09560

25 - Dirks, P. H., Roberts, E. M., Hilbert-Wolf, H., Kramers, J. D., Hawks, J., Dosseto, A., . . . Berger, L. R. (2017). The age of Homo naledi and associated sediments in the Rising Star Cave, South Africa. ELife, 6. doi:10.7554/elife.24231

26 - Dembo, M., Radovčić, D., Garvin, H. M., Laird, M. F., Schroeder, L., Scott, J. E., . . . Collard, M. (2016). The evolutionary relationships and age of Homo naledi: An assessment using dated Bayesian phylogenetic methods. Journal of Human Evolution, 97, 17-26. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2016.04.008

27 - Thackeray, J. F. (2015). Estimating the age and affinities of Homo naledi. South African Journal of Science, Volume 111(Number 11/12). doi:10.17159/sajs.2015/a0124

28 - Thorne, A. G., & Wolpoff, M. H. (1992). The multiregional evolution of humans. Scientific American, 266(4), 76-83. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0492-76

29 - Stringer, C., & Andrews, P. (1988). Genetic and fossil evidence for the origin of modern humans. Science, 239(4845), 1263-1268. doi:10.1126/science.3125610

30 - Sistiaga, Ainara, et al. “Microbial Biomarkers Reveal a Hydrothermally Active Landscape at Olduvai Gorge at the Dawn of the Acheulean, 1.7 Ma.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 117, no. 40, 2020, pp. 24720–24728., doi:10.1073/pnas.2004532117.

31 - Scarre, Christopher. The Human Past: World Prehistory and the Development of Human Societies. Thames & Hudson, 2018.

32 - Hora, Martin, et al. “Dehydration and Persistence Hunting in Homo Erectus.” Journal of Human Evolution, vol. 138, 2020, p. 102682., doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2019.102682.

33 - Pante, Michael, et al. “Bone Tools from Beds II–IV, Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania, and Implications for the Origins and Evolution of Bone Technology.” Journal of Human Evolution, vol. 148, 2020, p. 102885., doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2020.102885.

34 - Joordens, Josephine C., et al. “Homo Erectus at Trinil on Java Used Shells for Tool Production and Engraving.” Nature, vol. 518, no. 7538, 2014, pp. 228–231., doi:10.1038/nature13962.

35 - Hillert, Dieter G. “On the Evolving Biology of Language.” Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 6, 2015, doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01796.

36 - Hlubik, Sarah, et al. “Hominin Fire Use in the Okote Member at Koobi Fora, Kenya: New Evidence for the Old Debate.” Journal of Human Evolution, vol. 133, 2019, pp. 214–229., doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2019.01.010.

37 - Yravedra, José, et al. “Mammal Butchery by Homo Erectus at the Lower Pleistocene Acheulean Site of Juma’s Korongo 2 (JK2), Bed III, Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania.” Quaternary Science Reviews, vol. 249, 2020, p. 106612., doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2020.106612.

38 - Ingicco, T., et al. “Earliest Known Hominin Activity in the Philippines by 709 Thousand Years Ago.” Nature, vol. 557, no. 7704, 2018, pp. 233–237., doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0072-8.

Até à data, e do que é do meu conhecimento, isto é "tudo" o que eu tenho, mas penso que muito mais estará ainda por descobrir...Desde já grata pela atenção e com os melhores cumprimentos,Rosana Afonso(Divisão de Ambiente)Maria Pontes de Azevedo <maria.azevedo@aeso.pt> escreveu no dia quarta, 24/05/2023 à(s) 10:16:Bom dia, caríssima Rosana.Foi muito doa a palestra de ontem.Muito obrigada, ao Município de Lagoa, pela oportunidade.Entretanto desejava saber se tem, e se pode partilhar, referências acerca da navegação do homem primitivo por barco, até ilhas.Muito obrigada.

LIVE SOBRE A ORIGEM DOS 6 SONS! Você sabe o que é e de onde vieram os Seis Sons de Cura? Essa técnica poderosa tem origem muito antiga. Atravessou os milênios e hoje é uma prática que tem sido redescoberta e valorizada no combate a uma série de desequilíbrios. Vem para o Pérolas da China para saber mais! Tema: A Oregem dos 6 Sons de Cura Clique no link para acessar https://www.youtube. |

|

Abraços, Ana Horta Instrutora de Qi Gong e Tai Chi Chuan |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

..

by Gene Ching ![]()

April 25, 2022

China's venerated soft style of martial arts has two dominant spellings: tai chi chuan or taijiquan. It's confusing but both are correct. These are just alternate methods of romanization. Remember that Chinese is logographic, meaning that it is character based not alphabetical. In English, words are assembled from our 26-letter alphabet, which is what you are reading now. In Chinese, it's some 5000+ individual characters. When written in traditional Chinese, it is 太極拳; the spelling is a transcription.

This is the simple answer. Chinese culture is a Chinese box, filled with mysteries. When you open one box, you find another inside. YMAA Publication Center always seeks a deeper understanding of such matters, so let's open a few of tai chi's (or taiji's) Chinese boxes.

Tai chi chuan is the most popular spelling. Search it on Google and you'll get 230,000,000 hits. Taijiquan only gleans about 1,740,000 Google hits, however this spelling is used in scientific and academic journals because it is in pinyin, the official romanization system of Mandarin established in the 1950s.

Tai chi chuan is more prominent because of precedence. Wade-Giles is an older romanization system that dates back to the mid 19th century. There it is spelled t'ai chi'h ch'üan. This degenerated because few typewriters had an umlaut key for the ü (remember that computer keyboards didn't eclipse the limited typewriter keyboards until the 80s). What's more, only those familiar with German or Hungarian know what an umlaut does nowadays. Over time, the umlaut was abandoned, and the second H was dropped to t'ai chi' ch'uan, which is still seen in older publications. Then the accents disappeared leaving us with what we have today.

The variations between CH, J, and Q are more complex. 'CH' and 'J' are made with the same mouth shape, just with different voice onset times. Try this. Alternate making 'CH' and 'J' sounds, and you'll discover that the positions of your lips and tongue do not change. What changes is when you voice the sound. Different languages have subtle distinctions in parsing voice onset time. In Mandarin, chi (or ji) is right in between CH and J. If you can do that, your pronunciation is more accurate.

Q is confusing. Pinyin uses the Q for a slightly different CH sound, so it's not like the Q in quarter or quill, although it can be in Cantonese. Best not to dwell on this and just stick with the CH sound. The same problem afflicts qigong.

Speaking of Cantonese, the earliest Chinese immigrants were southerners and spoke that instead of Mandarin. Cantonese and Mandarin share the same general written language but sound completely different. Consequently, there's a different romanization system - Yale. Yale isn't used in martial arts circles very much so this spelling is unrecognizable - taai gik kyun. This kyun is more like the Q sound, but don't let that confuse you.

Tai chi chuan is conventionally translated as 'Grand Ultimate Boxing.' 'Tai' means 'very, too, much; big; extreme' so 'grand' is viable. 'Chi' means 'very, too, much; big; extreme' but it is more about embracing both polarities. More on this next. 'Chuan' literally means 'fist' but when placed as a suffix character, it refers to a style or branch of Chinese martial arts. So tai chi chuan is by definition a martial art. When the chuan is omitted, as it so often is in the West, it becomes something else – a fundamental Daoist philosophy. However in the common tongue, it is often just used to refer to the martial art both in Chinese and English now.

Tai chi is the proper term for what we typically call the yin yang ☯. In the simplest of terms, first there was void, or wuji 無極. When something emerges from the void, a duality is born because now there's something and nothing. This is yin yang, or tai chi (taiji works better here because it is the same ji character as in wuji). Ji is also translated as 'ridgepole' but here, it's more like the polarities of that pole. These polarities are yin and yang, empty and full, light and dark, or whatever complimentary opposites form a whole. That is an interpretation of ☯.

The martial art of tai chi chuan is an expression of this Daoist cosmological view that applies the philosophy to self-defense. By strict interpretation, tai chi without the chuan is not the martial art. It's this Daoist concept. However, within popular western vernacular tai chi commonly refers to the practice now and only a fraction of practitioners understands the Daoist connotations. Tai chi alone garners 3,930,000,000 Google hits. Taiji sans quan gets 11,100,000 but this is confounded by the town of Taiji, Japan. Although small, Taiji attracted global criticism because it is a whaling town, and its annual dolphin hunt was reported in the 2009 Oscar-winning documentary The Cove. Search Taiji news and you'll get as much about dolphins as you will about push hands.

Even more confusing, there are now two ways to 'spell' tai chi in Chinese. In the 1950s and 60s, China simplified the characters to promote literacy. The characters for tai and chuan remain the same but chi was simplified. The traditional character is 極; the simplified is 极. Note that both characters retain the same radical – the four strokes on the left side of the character. Radicals are the building blocks of more complex characters. This radical is mu 木 which means 'tree'. This is likely connected to the root ridgepole meaning.

Some of the Chinese diaspora reject simplified characters because it was a communist rectification, but it did do a lot to increase literacy in modern China. Many communities that fled the communists like the Taiwanese staunchly adhere to traditional characters. However, like pinyin, the simplified is official, so this is what is used in academic, scientific, and political publications.

When it comes to tai chi chuan versus taijiquan, that first generation of Cantonese immigrants adapted to survive. You seldom hear Cantonese masters advertise taai gik kyun. They've adopted tai chi, just like 3.9 billion Google users.

Perhaps someday, taiji will overtake tai chi in popular usage. Until that time, we must avoid being fixated, and perpetuate the practice no matter how it is spelled.

Editor's Note: This article is in honor of World Tai Chi & Qigong Day celebrated worldwide on the last Saturday of April.

https://ymaa.com/publishing/author/gene-ching

por Gene Ching ![]()

24 de abril de 2023

Se a disparidade entre as grafias de Tai Chi versus Taiji é confusa, Chi Kung e Qigong é ainda mais incômodo. Para reiterar o ensaio anterior sobre o tema , trata-se de como o chinês foi romanizado de caracteres logográficos para letras do alfabeto. Para começar, a capitalização não existe com caracteres chineses. Esse é um conceito estranho às linguagens logográficas. O chinês também tem alguns sons diferentes do inglês que não se encaixam perfeitamente nos sons descritos pelo alfabeto.

Chi Kung é a ortografia mais antiga e está mais próxima do som da palavra para falantes de inglês não familiarizados com a romanização pinyin. Qigong é a grafia pinyin mais recente. Em pinyin, o Q é pronunciado como 'CH' em 'chin'. Isso levanta a questão 'Por que o pinyin não usa apenas 'CH' para sons 'CH'?' Afinal, o CH é usado em palavras como Chin Na e Chen Tai Chi .

A distinção entre Q e CH em pinyin é sutil, quase indetectável para um ouvido não chinês. Tem a ver com onde você coloca sua língua. A maioria dos falantes de inglês deixa a língua plana ao expressar o som 'ch'. Para o pinyin Q, a forma da boca e a voz são semelhantes, mas a língua é enrolada para trás em uma posição mais alta contra a paleta rígida. Tente. Faça o CH soar como você sempre faz e tente com a ponta da língua começando no céu da boca. Faz um som ligeiramente diferente, algo fácil de perder se você não estiver sintonizado para ouvi-lo. O alfabeto não tem uma letra que possa acomodar essa diferença, então o Q foi usado desajeitadamente. É um compromisso irritante porque a vontade não iniciada de perguntar 'O que é kwee-gong?' Mas para quem tenta aprender mandarim, é uma distinção crítica.

Se o Google é usado como um barômetro de popularidade, Chi Kung é o termo mais popular. O Chi Kung obtém 39.800.000 acessos quando pesquisado, enquanto o Qigong recupera menos da metade disso, apenas 18.300.000 acessos. No entanto, o uso de Qigong está aumentando porque pinyin é o sistema oficial de romanização do mandarim. É o que se usa em qualquer tratamento acadêmico ou jurídico. Infelizmente, a disseminação popular do Qigong para o Ocidente é perpetuamente prejudicada por esse Q.

Assim como com Tai Chi versus Taiji, Qigong sofre de grafias diferentes (ou mais especificamente, logografias diferentes) em chinês também. Os comunistas simplificaram os caracteres chineses, então agora existem duas representações para o Qi – simplificado e tradicional. O caráter tradicional combina dois radicais. O primeiro é Qi (气), que pode significar vapor ou vapor. O segundo é Mi (米), que significa arroz cru descascado ou descascado. A combinação desses dois caracteres forma o caractere tradicional para Qi (氣), que, como a versão simplificada, também pode significar vapor ou vapor, bem como ar ou gás. Mais importante, também pode significar espírito. Muitos interpretam essa combinação como uma metáfora – o vapor que sai do cozimento do arroz. Aqui é onde fica complicado. O novo caractere simplificado remove o arroz. É apenas o primeiro radical. Sozinho, esse personagem é usado como a versão simplificada.

Além das letras e caracteres, Qigong é complicado de traduzir. Dos dois caracteres que compõem o Qigong, o Gong é fácil, então voltaremos a isso. Qi é desafiador. Assim como o inglês não tem um som para o pinyin Q, não há uma palavra análoga para Qi. No campo das artes marciais, o Qi é geralmente definido como uma energia universal, algo que circula por todas as criaturas vivas. É importante reconhecer que esta é uma definição pragmática. Como exemplo de exceção a essa definição, você pode dizer que algo inanimado pode ter um 'qi bom', como uma pintura, uma escultura ou qualquer obra de arte. Você poderia dizer que um espaço tem 'bom qi' se tiver beleza natural ou bom Feng Shui.

Dentro do chinês, Qi tem várias definições. Dicionários chineses modernos listam dezenas de definições; alguns incluem mais de oitenta usos diferentes. Ao traduzir chinês para inglês, fica complicado quando não há um único analógico. As tentativas de restringir a tradução do Qi deixam muito para trás. No entanto, todo praticante ocidental precisa de uma tradução básica do Qi para enquadrar sua perspectiva, então algo simples no início é melhor. Qi é um termo expansivo e quanto mais fundo você for, mais evasivo ele se torna.

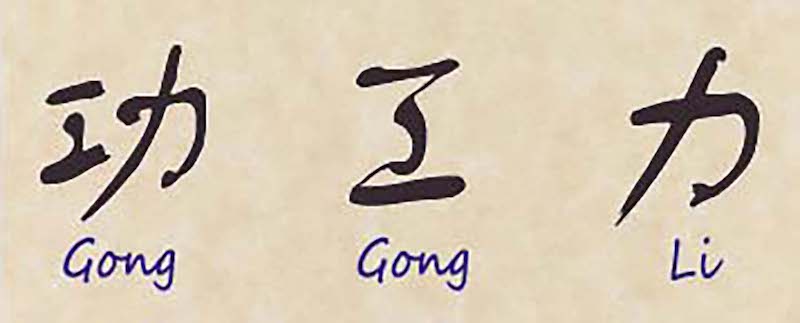

O Kung (功) do Chi Kung é o mesmo Kung do Kung Fu. Em pinyin, Kung Fu é gongfu. Kung (ou gong) combina dois radicais, gong (工) que significa trabalho ou trabalho e li (力) que significa força física, poder ou força. Combinado com gong (功), pode significar conquista, mérito ou bom resultado. Nas artes marciais, é convencionalmente traduzido como algo semelhante a 'habilidade alcançada com muito tempo e esforço'. Isso é um pouco prolixo para um personagem, mas eu admiro a poesia dele.

Gong já é um caractere simples – apenas cinco golpes – então não há uma versão simplificada moderna. Compare isso com o Qi tradicional, que é de dez golpes. Retire o arroz e reduz a apenas quatro golpes.

No artigo anterior , foi explicada a história da ortografia convencional do Tai Chi, justaposta à versão pinyin do Taiji. Tai Chi é o termo mais familiar. Usando o barômetro do Google, a contagem de acertos para a ortografia do Tai Chi supera todas as outras na ordem de 230.000.000. Com Chi Kung chegando a 39.800.000, Qigong a 18.300.000 e Taiji, apenas 1.740.000, ele ganha uma posição no título.

No entanto, igualar os dois ganhadores de maior sucesso também não funciona. O Dia Mundial do Tai Chi Chi Kung é lido horrivelmente com o Chi duplo. Também é enganador porque o Chi no Tai Chi e o Chi no Chi Kung são duas palavras completamente diferentes. É por isso que é Ji e Qi em pinyin. O Dia Mundial do Taiji Qigong é o mais progressivo, mas dado que a ortografia do Tai Chi domina a ortografia do Taiji em quase 230 vezes, isso não é 'otimizado para mecanismos de busca' e, no mundo de hoje, é tudo sobre SEO.

Isso demonstra onde estamos no mundo com a divulgação dessas artes. Várias complicações surgem ao traduzir até mesmo nossos termos mais fundamentais do chinês para o inglês. Há caracteres simplificados versus tradicionais. E depois há a romantização vacilante. Mas o mais significativo é o significado exato das palavras. A coisa mais importante a entender sobre tradução é que nem sempre é uma equação X=X. Às vezes X=Y+Z. E outras vezes, não há equivalente simples.

É uma reminiscência daquela velha canção Ride the Tiger de Jefferson Starship:

É como uma lágrima nas mãos de um homem ocidental

Falar sobre sal, carbono e água

Mas uma lágrima para um homem chinês

Ele vai falar sobre tristeza e tristeza ou o amor de um homem e uma mulher

Para quem é novo no campo, o mais simples é o melhor. E a cultura pop se contenta com uma resposta simples. Para os mais estudiosos, a tradução pode ser uma viagem a si mesma, uma profunda toca de coelho a ser explorada com perspicácia e admiração.

O Dia Mundial do Tai Chi Qigong é observado no último sábado de abril. Para 2023, isso cai em 29 de abril.

O texto acima é um artigo original de Gene Ching, redator da equipe do YMAA Publication Center.

Gene sits on the Advisory Boards of Rock Medicine and JMED, two separate organizations devoted to providing medical care at concerts, gatherings and music festivals. His expertise is in the deescalation of intense psychedelic reactions. Beyond YMAA, Gene also writes for KungFuMagazine, Den of Geek, and UNESCO ICM. Gene resides near San Francisco CA.

Prezada Maria, Obrigado por se inscrever no curso Descubra o Yi Quan Qigong para Saúde, Clareza Mental e Longevidade com Ken Cohen. Seu ...